Lessons from "Fires in the Mind"

What does it take to get really good at something? For the past two years, I have used this simple but compelling question to draw students and teachers together in a mutually rewarding exploration of motivation and mastery.

Powerful new evidence from cognitive psychology shows that opportunity and practice have far more impact on high performance than innate talent. We now know that 10,000 hours of “deliberate practice”—focused attention on just the thing one needs to learn at that point—go into making someone an expert.

But what motivates students to engage and persist in the arduous practice that results in such mastery? To find out, our national nonprofit What Kids Can Do (WKCD) set out to ask adolescents themselves.

Supported by MetLife Foundation, the Practice Project initiative drew in hundreds of ordinary students from diverse backgrounds around the United States to explore how young people acquire the knowledge, skills, and habits that help them rise to excellence in a field. The resulting book, Fires in the Mind: What Kids Can Tell Us About Motivation and Mastery

uses the voices of these young people to shed light on powerful teaching and learning wherever it takes place.

At first, students’ examples seemed to come overwhelmingly from experiences outside school: music, dance, drawing, drama, knitting, chess, video games, running, soccer, building robots, braiding hair, writing poems, cooking and skateboarding. The kids shared what drew them into these activities and described the satisfactions that kept them going despite the hardships of long hours of practice.

As we learned why these students engaged so deeply in extracurricular work, we wondered how teachers might transfer the excitement and satisfaction of mastering a challenge into the classroom. Could what these young people already understand about practice transform their academic learning as well?

Though they knew they were “getting good” in outside activities, the students did not express this same confidence in relation to their schoolwork. “Whatever we’re studying, we won’t be experts yet in that field,” Kenzie told me. Based on their outside experience, students felt that to build their base of knowledge and to practice important skills across the curriculum would clearly take a lot of focused time, effort, and coaching.

Yet the structure of school seemed to undercut that possibility. Class time that was fragmented into disconnected subjects presented in short blocks of time did not give kids the “deliberate practice” that most deeply engaged them. Often they did not see the value or meaning in their everyday schoolwork; similarly, typical homework assignments did not help them make this connection or move toward mastery.

Interdisciplinary curricular projects, however, stood out for them as a marked exception. Like their most compelling activities outside of school, these hands-on units often had students working toward an outcome that mattered to them. Because kids valued the project’s goal, they willingly went after the knowledge and skills required to reach it. Along the way, they put what they were learning into use, and when they ran into trouble they received encouragement and help.

For many kids, the draw was often simply that a project looked like fun. Actively working on a “real world” problem with their peers was particularly appealing to them. Even if the topic did not immediately grab them, a group exploration to build new knowledge held much more interest than a classroom lecture.

“You end up asking a lot of questions,” said Tyler, whose high school biology class set out to create DNA barcodes for endangered species in the African bush. “And because you have to ask questions, you end up learning a lot.”

Often the culminating goal of the project—a trip, a performance, or a competition—lent the group energy and purpose from the start. “Everyone cares, because it’s a real thing,” said Alex about the one-act play his English class wrote and produced. “We have to get it done, so there’s that need to work together.”

As with an athletic team or a musical ensemble, students saw their individual strengths as a vital part of the success of the project. The more they felt that their contribution mattered, the more motivated they were to do it well. “Your group depends on you to get that task done,” said Erika, whose class trip to Washington, D.C. involved extensive interviews on Capitol Hill and at embassies. “If one person doesn’t do their job, the project will fail.”

Teamwork, they realized, helped generate a kind of “group expertise.” Ruben explained, “What I may not be able to do, somebody else can. If I need help, I go to them, and if I can do something that other people can’t, they are going to come to me.”

To do a good job on these projects, students needed deliberate practice in negotiating the dynamics of a working group. The teamwork challenges are considerable, said Kristian, whose San Antonio school grounds its curriculum in projects.

“We have to work in groups with people we may not necessarily want to be with,” she said. “You could have a struggle for leadership, like: ‘Who’s gonna take charge of this project?’ You have to look back at other experiences and figure out, ‘How did I do it in this situation? How did I work with somebody that gets on my nerves?’”

Teachers at that school explicitly coach students in collaboration skills from ninth grade on. “We were taught a lot of skills, like how to come to consensus,” Erika explained. “We had a whole lesson about whether or not a group should vote on things.”

Like team projects in the world of work, these school-related projects required participants to gather and use knowledge in many different ways. Students were simultaneously using their individual strengths and growing in understanding from the work that others were doing.

Here again, teachers played an important coaching role. For example, when assigning research tasks to build the team’s base of knowledge, teachers took care that students at every level could expect to manage them successfully.

“We started with baby steps and worked up, year by year,” Bridget explained. “First it was, ‘Here are the articles; this is the information you should gather.’ Then, ‘Here’s where you can find the information,’ and then, ‘This is the question I want you to find.’ Finally, it was, ‘Have fun, go for what you want to find out.’”

Students also learned to utilize less conventional sources of information, such as accessing expertise within the community. “We had to contact people and negotiate with them, and put things together,” said Nick. “That wasn’t easy, but we all were expected to learn.”

In a regular classroom routine, students shared their growing knowledge with others on their project team. “We had weekly or so meetings and sometimes we would have what we call ‘Big Teach,’ when the class all comes together and we divide into our groups,” said Aaron. “The teacher was just there to facilitate it, to make sure these things were done in a timely fashion.”

Team projects encourage students to build individual skills and help their peers rise to excellence when:

As they combined their knowledge in such ways, students began to realize that they were generating new knowledge and making new sense of what they learned. And in that process, they were finding new intellectual satisfactions in the company of their peers.

“When we make a project together, it’s not just one person saying, ‘We should do it this way,’” Ruben said. “Everybody is putting in their own little input, and the final thing that you make will be everybody’s together.”

The excitement of exploring new territory together, students said, helped them keep up the work even when it grew difficult and intense. With supportive adults to coach them in the skills they need, collaborative project work can engage all students in the flow that Molly felt during the last stages of a robotics project.

“You really don’t notice when you’re here for two days straight, because you’re working on finishing,” she said. “It becomes something that you’re so proud of. Finally, after you have left whatever project you have been working on, you go home and you’re still thinking about it. That’s the last thing you think about before you sleep.”

Creative Educator can help you bring project-based learning to your school.

Learn More8 first projects to get students using technology

Creative, digital book reviews

Fun and powerful ideas with animated characters

Wixie

Share your ideas, imagination, and understanding through writing, art, voice, and video.

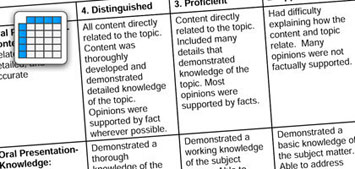

Rubric Maker

Create custom rubrics for your classroom.

Pics4Learning

A curated, copyright-friendly image library that is safe and free for education.

Wriddle

Write, record, and illustrate a sentence.

Get creative classroom ideas delivered straight to your inbox once a month.

Topics